6 ways you can support your cervical health

When it comes to the topic of fertility you may not give much thought to your cervix. We tend to talk freely about heart health, mammograms and trips to the dentist. But rarely do we talk about cervical health. However, understanding what cervical health means, and following these six tips to proactively care for it now can help you best advocate for your cervical health.

1. Understand why your cervix is important

Pop quiz: Where is your cervix, and what does it do? If you’re struggling to recall the answer, you’re not alone. The first step in caring for your cervical health is learning about the important role your cervix plays.

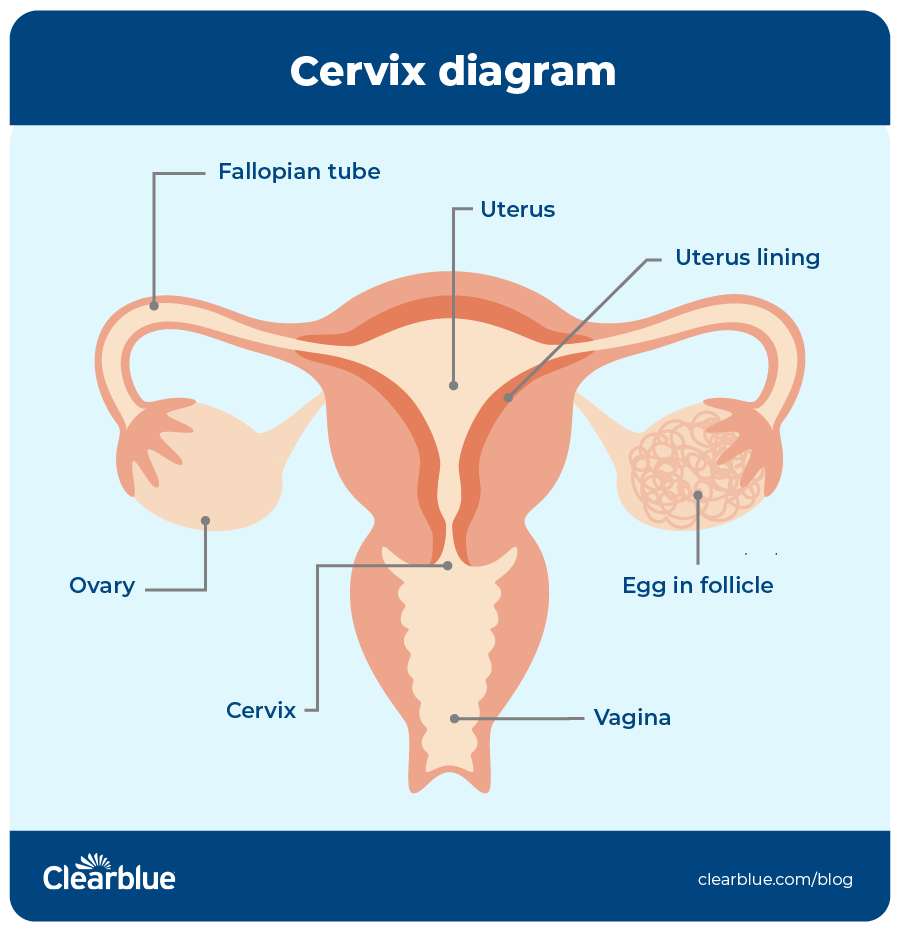

The cervix is a canal that connects your vagina to your uterus.

Your cervix plays several critical roles:

- It keeps bacteria in the vagina from entering the uterus.

- It serves as a canal for sperm to travel in toward the uterus and on to the fallopian tubes.

- It produces mucus that helps sperm move along the cervix to reach the egg.2

- It has a small opening that allows menstrual blood, traveling from the uterus, to exit via the vagina.

- The cervix helps maintain pregnancy until labor.2 When women talk about losing their mucus plug during pregnancy, they’re referring to the increase in vaginal discharge that happens when the cervix begins to dilate at the onset of labor, or even several days before.3

2. See your gynecologist regularly

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that you see your ob-gyn at least once a year. This appointment, similar to a yearly physical exam, is a good opportunity to discuss a wide range of issues related to your gynecological and reproductive health. Yearly checkups will also ensure you receive proper cervical care.4

3. Get regular Pap smears and HPV tests

If you’ve never had a Pap smear (also called a Pap test) or HPV test before, rest assured that it’s a simple procedure. While it may feel a bit uncomfortable, it shouldn’t hurt. After the procedure, the cells are sent to a lab and examined under a microscope for signs of cervical cancer or cell changes that may become cervical cancer if not treated appropriately, called precancers.5,6 The HPV test looks for the human papillomavirus, which can cause cell changes that can lead to cervical cancer.6

Many women no longer need to get a Pap smear every year. These are the latest guidelines, according to ACOG and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC):3,7

- 21 to 29 years old: If your Pap smear result is normal, you may be able to wait three years until your next test.

- 30 to 65 years old: Talk to your ob-gyn about which option is best for you:

- Pap smear only: If your result is normal, you may be able to wait three years until your next test.

- HPV test only: If your result is normal, you may be able to wait five years until your next test.

- HPV test plus Pap smear: If both results are normal, you may be able to wait five years until your next test.

Your doctor may require more frequent screenings for several reasons, including a weakened immune system and a history of cervical cancer.3

4. Consider the HPV vaccine

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 42 million people currently have an HPV infection type that causes disease, and 13 million Americans become infected each year.8>/sup> ACOG reports that most of the 40 different types of infections that affect the genitals are asymptomatic, which is why the virus spreads so easily.9

Having HPV won’t affect your chances of conceiving,10 and treatment for precancerous cells that grow on the surface of the cervix won’t affect fertility.11 However, there may be a link between abnormal sperm and HPV-infected men.12 HPV can cause several types of cancer, which can take years, or decades, to develop.13

The infections that cause most HPV cancers in young adult women have dropped 81 percent since the vaccine was first introduced in the U.S. in 2006.14,15 And among vaccinated women, the percentage of cervical precancers caused by HPV types most often linked to cervical cancer has dropped by 40 percent.15

The CDC recommends that anyone through age 26 get the HPV vaccine if not fully vaccinated already.15 If you are 27 through 45 years old, talk to your doctor about whether the HPV vaccine is right for you. According to the CDC, the vaccine provides less benefit to adults simply because more people in this age range have already been exposed.15

5. Know common cervical cancer symptoms

Most HPV infections go away on their own thanks to our body’s natural defenses, with only mild changes to the cervical cells. The cells then go back to normal once the HPV infection clears.16 For a small number of women, however, a high-risk HPV infection that persists can cause more severe changes to their cervical cells and, if left untreated, has been reported to lead to cervical cancer.16

Even though cervical cancer may not cause any symptoms early on, advanced cervical cancer may cause abnormal discharge or bleeding.17 If you experience these symptoms, it’s important to see your doctor as soon as possible.

6. Pay attention to your discharge

Typically, cervical mucus changes throughout your cycle. Prior to ovulation, the mucus is thick and white. This type of mucus sometimes referred to as “infertile cervical mucus.” Just before ovulation, the mucus becomes slippery and elastic, allowing sperm to move more easily into the uterus to the fallopian tubes.18 This mucus type is sometimes called “fertile mucus.” If you have questions about the different types of cervical mucus and what they may indicate about your ovulation cycle, talk to your doctor.

Great strides have been made to protect women’s fertility and address cervical health challenges. When it comes to your cervical health, the No. 1 thing you can do now is be proactive — and the best time to start is now.

Sources

- “Cervix,” (January 1, 2021), National Library of Medicine, https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/002317.htm.

- “F. Martyn, F.M. McAuliffe, M. Wingfield, (October 10, 2014), “The role of the cervix in fertility: is it time for a reappraisal?,” Human Reproduction, 29(10), 2092–2098, https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deu195.

- “What does it mean to lose your mucus plug?” (October 2020), The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, https://www.acog.org/womens-health/experts-and-stories/ask-acog/what-does-it-mean-to-lose-your-mucus-plug.

- Mutch, D., “Why Annual Pap Smears Are History – But Routine Ob-Gyn Visits Are Not,” (April 2021), The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, https://www.acog.org/womens-health/experts-and-stories/the-latest/why-annual-pap-smears-are-history-but-routine-ob-gyn-visits-are-not.

- “Pap smear,” (n.d.), National Cancer Institute, https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/pap-smear.

- “Cervical Cancer,” (January 12, 2021), Center for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/cervical/basic_info/screening.htm.

- “Cervical Cancer: What Should I Know About Screening?” (January 12, 2012), Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/cervical/basic_info/screening.htm.

- “Human Papillomavirus (HPV): HPV Infection,” (July 23, 2021), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/about-hpv.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fhpv%2Fparents%2Fwhatishpv.html.

- “Human Papillomavirus (HPV): HPV Infection,” (July 23, 2021), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/hpv-vaccination.

- “Human papillomavirus,” (March 22, 2019), Office on Women’s Health, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, https://www.womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/human-papillomavirus.

- Kyrgiou, M., Mitra. A., Arbyn, M., Stasinou, S.M., Martin-Hirsch, P., Bennett, P., et al, “Fertility and early pregnancy outcomes after treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: systematic review and meta-analysis,” (October 28, 2014), BMJ, (349)6192, https://www.bmj.com/content/349/bmj.g6192.

- Jeršovienė, V., Gudlevičienė, Ž., Rimienė, J., & Butkauskas, D, (2019), “Human Papillomavirus and Infertility, Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania), 55(7), 377, https://www.mdpi.com/1648-9144/55/7/377.

- “Human Papillomavirus (HPV): HPV Fact Sheet,” (January 19, 2021), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv.htm.

- “Hysterectomy,” (January 2021), The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/hysterectomy.

- “Human Papillomavirus (HPV): HPV Vaccine,” (July 23, 2021), Centers for Disease Control, https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/vaccine-for-hpv.html.

- “Cervical Cancer Screening,” (May 2021), The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/cervical-cancer-screening.

- “Cervical Cancer: What Are the Symptoms?” (n.d.), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/cervical/basic_info/symptoms.htm.

- Rebar, R.W., “Problems With Cervical Mucus,” (September 2020), Merck Manual, https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/women-s-health-issues/infertility/problems-with-cervical-mucus.